Children of earth and starry sky—

threshed from a stalk of wheat,

scattered,

thirsty for Mnemosyne.

—Author unknown

Beneath New Harmony lies the western fringe of a vast limestone realm, riddled with hidden streams and passages—including the world’s longest cave system lurking to the southeast.

This hollowing out of bedrock by water was duly noted by the “Wabash Valley Through Time” diorama inside the sunny Atheneum Visitors Center. Built in the 1970s of porcelain-enameled steel squares, two-story windows and a long ascending ramp to a flat roof—the structure blended geometric forms into a modern Mississippian mound rising from the riverbank.

“Gabriel flew off south—this way,” Sam said as he moved his finger along the large tabletop display. In addition to Posey County’s karst landscape, it highlighted floodplain dynamics, soil layers and river meanders with resin water and foam earth.

“You start getting into cypress swamps 15 miles downriver,” Di said. Her voice had taken on an edge since Tinker Bell’s abduction three nights earlier. “I’m getting a strong feeling from those trees about something. That’s where I should be now. We’re not going to learn anything from this.”

Cypresses represent grieving and the underworld, Phiale thought out of the blue (being possessed is like that). Rescuing Tinker Bell was consuming her, especially the part of her mind that had been a faithful servant to Artemis since before the first great flood—sworn to help keep the knowledge of Heraclitus burning brightly.

“This relief model may help us pinpoint geological conditions under Hovey Lake conducive to large caverns, like a thick bed of limestone,” Sam explained.

Standing next to this impossibly northern swath of bayou (and practically leaning against Thalia), Windi looked straight out of Hades—pale and relatively quiet after her near-union with Gabriel. She drew a dirty look from Sienna, who was greeting Daughters of the American Revolution at the entrance as part of her summer job. Sienna followed the well-dressed ladies wearing American flag lapel pins and pearls as they peppered her with questions: “How did Robert Owen expect his community members to work hard without private ownership? Form bonds without religion? Thrive under neglected leadership?”

“Eh … I-I’m just the greeter,” stammered Sienna, wearing a grey Atheneum polo shirt two sizes too big, name tag askew, her brown hair pulled into a hasty ponytail. “The guide hasn’t shown up yet.”

“Good morning, mesdames, enchanté,” Sam said, bowing deeply. “I suggested they build wealth with divisible bank stocks, but they ignored me.”

“Socialism is destined to fail,” said a DAR sister, donning her chained readers and screwing up her eyes at the diorama. “Is this a child’s project? Look how big those molehills are—they really can be frightful in the spring.”

“Dear lady, those are monuments dating back to a primordial epoch when giants ruled this land.”

Sienna groaned and shot a glance outside.

“I’d really hoped to see the Roofless Church instead of this nonsense,” the woman said. “They had it roped off because of some kind of gas line explosion.”

“Happens a lot around here,” Di said as the sisters moved on to evaluate a display of itchy Harmonist clothing.

Sienna lingered. “You all know about the giants?”

“Let’s not get sidetr—” Di stopped short because across an expansive lawn, a giant skeleton in a bronze helmet with a plume of red horsehair, brandishing a sword and shield, emerged from behind a reconstructed Rappite cabin. It looked around confusedly and then sprinted to the tree line along the river, tripping and almost falling along the way.

“They didn’t come back right,” Sienna said, crying. “It was my f-f-fault. Mr. Owen kicked me out of the Seance Club … that’s OK … I’d rather do 4-H anyway.”

“It’s for the best,” Thalia said, putting a hand on her shoulder. “Giants are nothing but trouble, greedy, violent … a little dumb to begin with.”

“Tell us what happened,” Di said.

“Well, I guess I should go ahead and say, before somebody gets hurt. We brought them back two weeks ago, on the night of the Flower Moon … ”

***

Sienna’s jeans were soaked from the knees down as the Seance Club crept through the misty cornfield surrounding the Emerald Mound Acropolis. A din of crickets and peepers pulsed in the clammy night.

Mr. Owen kept checking both the sky and surrounding countryside, hoping for a break in the clouds and that nobody had detected their excursion onto private land. The distant glow of St. Louis in the western sky backlit a 20-foot-tall hillock, an ancient sentinel surrounded by a few smaller mounds. Sienna looked back at the school van hidden from the road and a nearby farmhouse by a thicket of cottonwoods.

Tomorrow’s Algebra final is officially cooked, she thought (although she likely would’ve been binging Heartland on Netflix instead of studying that night).

Once they reached the tree-covered Emerald Mound, Mr. Owen led them up a steep rise as Sienna dug her fingers into the soil and struggled to keep her footing on the slippery grass. Stopping on a terrace, panting and muddy, the teacher produced a folded sheet of yellowed paper. The words “Ancient Lunar Temple” danced under his shaky flashlight beam. “Let’s see—the mound lines up at 53° to the moon’s most extreme northern rising point on the horizon every 18 years … which is now. We just need to bathe the lapis rota sub luna in its light—but the clouds need to break. We’re on the right side, facing east. We just have to unearth the chamber cap.”

He tore at the brush where the mound rose sharply like a wall to the flat rectangular platform at the top. “Help me dig.”

Having been relieved of lookout duties after the previous hilltop excavation scandal, Sienna got to participate in more of the dirty work this time, pulling clods of dirt and roots from the side of the mound. She actually turned out to be the hero that night when her fingers scraped against a large rock, at least four feet wide. “I might have found it,” she said.

“Good job, Sienna.” (It wasn’t a phrase Mr. Owen had reason to utter before.)

“Bellatrix, give me a crowbar,” he said. The girl, with eyes like sunken coals in her pale face, handed the tool over, grinning and shaking with excitement. Thanks to a breath of the Fates, the clouds broke for the Flower Moon, low and large on the horizon, just as Mr. Owen worked loose the limestone slab. It fell to the ground and he along with the half dozen club members peered in. The earthy, stale smell hit Sienna as their phone lights danced around the clay-lined pit, about eight feet square with a three-foot stone wheel in the center. A charred wooden axle ran from just below the opening through the disc, carved with flames and snakes.

“Turn your lights off,” Mr. Owen said. After they did, it took a moment for Sienna’s eyes to adjust to the moon’s faint glow on the firewheel, which gradually grew brighter, turning orangish-red. Then it creaked, now spinning fast enough to kick up a plume of dust. Flames flickered along its rim.

Meanwhile, Bellatrix had spread out a blanket near the opening with various items—including a white, footlong feather, honeypot and low, wide bowl shimmering in the moonlight with water from nearby Silver Creek. The Seance Club gathered in a semicircle around the blanket. “Let’s not screw this up, girls, we don’t want them coming back wrong,” Mr. Owen said.

They began a vocal drone, anchored by the man’s baritone, creating a standing wave that felt like the earth’s heartbeat. Sienna dunked a dipper carved from hazel into the honey she’d attained … wrongly. Mr. Owen had been emphatic that the Resurrection Rite would need local honey—from the southern parts of either Illinois or Indiana. She had bought it from a thrift store, and it was labeled “local honey.” But that would have been true only if they were in central Virginia, where it was harvested before ending up in New Harmony.

See, honey absorbs biophotonic memory light from plants. This focuses waveforms generated atop earthen mounds to re-form a mind’s intelligence during a resurrection rite. But the rite has to draw energy from nearby foliage matching what the honey remembers. (At least that’s what Mr. Owen inferred from ancient Greek rites.)

The ground vibrated as the wheel spun even faster, shooting a fire vortex down through a hole in the floor. Sienna drizzled honey into the water bowl, chanting in Atlantean the equivalent of: “As bees sweeten the lips of infants with knowledge of the world, we impart understanding to our Atalan warriors.”

Mr. Owen shouted into a cellphone to an Adept in the granary: “It’s happening. The ley line is sparking now.” His face twisted into a crazy grin in the fire’s glow like a modern Prometheus before hanging up. “One of their fingers is twitching!”

Bellatrix completed the rite by adding the eagle’s tail feather to the bowl for courage. Then the teacher warned, “Keep an eye out for other effects. We just energized several nodes including the main one in Cahokia.”

“Like the procession?” yelled the lookout from atop the mound. Sienna clambered to the apex along with the rest of the group. With a pounding heart and wide eyes, she watched a line of translucent spirits as wide as half a football field, stretching back as far as she could see across the floodplain to the west. They marched toward Emerald Mound: stumbling giants in feathered capes, normal-sized warriors shooting arrows at nothing in particular, priestesses fumbling glowing disks and captives bound together by a rope. What are they for? Sienna thought. Then, just as the horrifying answer began to form, someone shouted: “Hey! What the hell’s going on up there?!”

“It’s the farmer,” Mr. Owen hissed.

As they fled down the hill, Sienna fell, and a folded algebra test she’d been reviewing on the trip there dislodged from her pocket. Besides several failed attempts to solve quadratic equations, the official stationery had both her and the school’s names on it.

***

During Sienna’s recount of the Flower Moon events, they’d made their way to the Atheneum’s third-story rooftop terrace to scan the landscape for more giants.

“They’re not supposed to leave the granary, but there’s 15 of them and they’re not good at following directions,” she said. “They’re better after we sing to them, though.”

“You literally sing to them?” Windi said. “And I thought the Butterfly Club was deranged.”

“More like humming. Mr. Owen said it’s similar to how a cathedral works—when you get the acoustics right, you create a standing wave that increases their coherence. Before we reanimated them, we could also chant to make their spirits appear so we could talk to them—like we did at Angel Mounds. The granary works, but Mr. Owen said there’s some chambers big enough to do it better in Mammoth Cave—what’s that room called … they have concerts in there … oh, it’s that weird guy … ”

“Rafinesque’s Hall,” Sam said. “I’m familiar with the ritual—remote communication with the living or dead.”

“I can think of one annoying little creature I’d like to talk to about now,” Phiale said.

Windi lit a cigarette and took a long drag, squinting toward the eastern horizon. “Looks like we’re going on another field trip.”

***

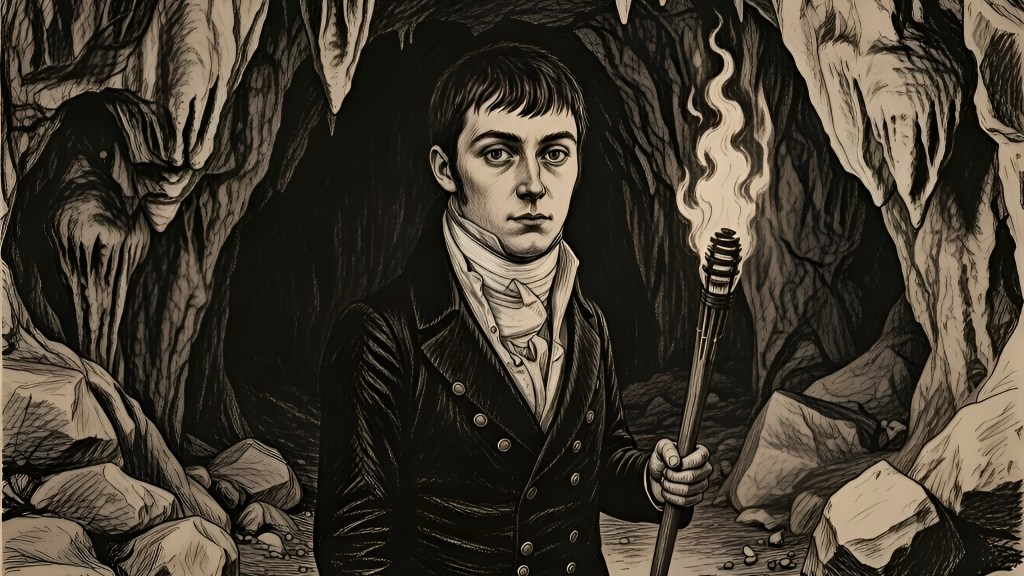

Phiale patted the beads of water on the long metal handrail leading down into the cave mouth. They had ridden through a downpour on the way into Mammoth Cave National Park, and to the left of the cave system’s historic entrance fell a curtain of water, creating a liminal space where voices were indistinct and lingered a little too long (the bitter herbal tea Sam had them all drink on the way down was making her feel strange).

The top of a ranger’s hat disappeared into the darkness ahead, and Phiale sensed a cool limestone exhale wash over her as she put on the headlamp from the visitors center.

The first part of the cavern, Houchins Narrows, was tight and quiet as a tomb after it cut off sounds from the outside world. Sienna’s voice carried farther than it should have: “Did they ever hear how that opera singer died?”

Thalia: “Yeah, heart attack, I’m cleared. Speaking of, I hope we don’t see any dwarves down here.”

Windi: “Why’d we have to bring Sienna along? She’s bad luck.”

Sam: “Shh! We can all hear you in here.”

Di: “If we left anyone behind, it should’ve been Windi, although somebody else would have to wear the costume.”

Windi: “I’m not going to wear that costume.”

Phiale: “She’s cranky because we couldn’t eat meat for the past three days.”

Sam: “Shed Titanic flesh, reveal the Dionysian spark.”

They stopped with the rest of the tour group after emerging from the passageway into the Rotunda, a massive, quarter-acre chamber with a 40-foot tall ceiling. Bats fluttered overhead.

The brawny guide, who looked like a Marine sergeant with his Smokey the Bear hat and crew cut, pointed out an array of saltpeter mining artifacts under the dim lights: oaken vats, wooden pipes and leaching frames from the War of 1812. Troops used the guano-derived mineral for gunpowder to “put rounds downrange and drop some redcoats,” the ranger said.

“Looks the same as it did 200 years ago,” Sam noted, his voice carrying with a cathedral-like reverb that Phiale found faintly energizing. “You’d think they could’ve cleaned this place up better by now.”

“What was that?” the guide said sharply.

“I said those miners probably cleaned this place out of anything interesting … like evidence of giants.”

“What about giants?” said a boy of around 10 accompanied by his grandmother.

“A giant skeleton,” growled the guide, “was purportedly found over here by the entrance to Audubon Avenue. Eight feet tall, massive jawbone.”

“Typical Atalan bone structure,” Sam told the boy.

“Were there really cave giants?” the boy asked his grandma as she pulled him close.

“Of course not, sweetie. Do be quiet.” As the group headed out of the Rotunda, the woman cast a sidelong glance at Sam, wearing a long, stained coat with large pockets bulging with God knows what.

“There were most certainly giants here, ma’am,” said Sam, chasing after them. “There were two major floods around 13,000 years ago, scattering them from an Atlantean outpost in North Africa to Atala, which sank under the wav—”

“Stand down, sir,” the guide interrupted, coming between Sam and the woman he was ranting at.

“So they retreated underground!” Sam stood on his tiptoes and shouted over the man’s broad shoulders. “To the only cave system big enough to accommodate them.”

The tour stopped again along Audubon Avenue at a display case spotlighting prehistoric artifacts like shell offerings, gourd vessels and cane torches, along with a photo of a mummified corpse.

“Is that real?” the little boy asked, pointing to the picture.

“That’s affirmative,” the guard responded. “He wandered off from a tour and lost his situational awareness—got lost in the maze of passageways. It goes to show that caves aren’t amenable to human life. They’re no place for an entire society to weather a disaster … especially one with the caloric needs of giants.”

Sam winced at the group’s laughter. “What about this?!” He pointed to a patch of fuzz growing on the wooden base of the lit case. Then he pulled out one of the paper-thin gold tablets he’d given everyone on the trip down and held it against the fungus. It glowed bluish-green for a moment, then emitted a golden light. “A variety of foxfire. Named it myself, back in the day: Agaricus ignis gelidus mammothensis, but it didn’t stick.” He frowned and shook his head. “Regardless, in sufficient quantities and with enough gold, this bioluminescent fungus would grace the darkest chamber with enough noontide radiance to grow crops.” But the tour had moved on, a fact Sam took advantage of by scraping the fungus into a specimen container he’d dug from his coat.

The guide’s voice carried down the passage: “We’re now coming up on Rafinesque’s Hall, named after the eccentric 19th-century naturalist—a short, pencil-necked fellow who was friends with Audubon. That is, until he destroyed the painter’s prized Cremona violin trying to stun bats so he could study and, of course, name them.”

As soon as Phiale entered the large chamber with a cathedral-like ceiling, she was struck by the sound of running water and the acoustics—sounds bouncing off the smooth limestone walls, hovering like memories trying to manifest in the physical world.

“Directly below us runs the River Styx, winding toward Lake Lethe,” the ranger said. “Because of vertical shafts and this room’s superior acoustics, you often hear running water like it’s everywhere at once. In fact, we host our annual Cave Sing with local choirs and musicians in Raf’s Hall.”

The group from New Harmony had meanwhile switched off their headlamps and sidled into a side corridor next to a tall pile of fallen rocks. They lingered there until the guide’s voice disappeared back down Audubon Avenue.

“Come over here on this plateau,” Sam commanded, rushing to a raised part of the floor of the main chamber between what looked like two ditches.

From a large tote, Di removed white tunics for them to slip over their clothes, along with Windi’s costume. “I said I’m not wearing that,” the girl muttered.

“Nonsense,” Sam snapped. “Put it on—we don’t have much time until the next tour arrives.”

Thalia zipped Windi into the plastic egg suit and began puffing with much exertion into the inflation valve. “Let me do it,” Di said, pushing her out of the way. Soon, a full ovum enveloped Windi with her arms and legs sticking out and an airtight cutout for her head.

“Now sit around the cosmic egg, and read from your gold lamellae,” Sam said.

“I am a child of Earth and starry sky … ,” Phiale chanted along with the rest. “ … twice born of the ever-living fire … torn apart but now re-membered … ”

Sam struck a tuning fork with a hammer and sang a droning low C. Thalia joined in an octave higher and the others tried to match it. Phiale’s breath made visible sine waves in the cold, damp air. She felt like she was dissolving and re-forming more powerfully.

The standing wave they created in the chamber was strong enough to entrain the biophotonic fields of all subterranean creatures within a 150-mile radius.

Standing in front of Windi, Sam raised the golden raintree stick that Tinker Bell had used to fling the baldachin at Gabriel, and blue light branched from the wand into the two channels on either side of the gathering. Water began flowing through both of them.

Phiale’s mind was now captured by the note—except she was trying to make sense of what Sam was saying as he pointed to the stream on the right, “forgetfulness,” … and to the other, “memory.” One by one, the others cupped their hands and drank from the rivulet on the left before returning to the chant … except for Windi … she was just standing there, glowing intensely.

Phiale suddenly felt incredibly thirsty. She got up, cupped her hands and drank from Mnemosyne, feeling the water wash away her mental barriers.

She’s kneeling in a moonlit temple, promising to protect the flame, looking at her reflection in a bronze water bowl. Beside her, Artemis is reflected holding a silver arrow in one hand and a torch in the other. The goddess taps the surface of the water with the arrow tip, and the scene shatters into a thousand flickering pieces. Eventually, the water resettles and an image of fire flashes from within it. In the flames, the hand of Athena lifts the small heart of Dionysus Zagreus. An oath is sworn by the blaze itself.

There was another flash—this one overhead—energy arced across the cavern’s ceiling and concentrated a few yards in front of the group. What looked like a ball of swirling flames coalesced into the likeness of Tinker Bell in an elaborate bird cage, squinting through the narrowly spaced bars. “Windi? Is that you?” she said. Then the fairy doubled over with laughter. “You look like you’re having another egg-setential crisis! You crack me up!”

Chapter 12 gets lit April 1. Read Part 1 on Kindle or in paperback. (Catch up with the Prologue.)